After Botani died unexpectedly, in 2010, Piratbyrån decided to disband. But The Pirate Bay still thrives, despite an ongoing criminal case against its operators. And in 2006, Rick Falkvinge founded Sweden’s Pirate Party, a political party that runs on a pro-Internet platform, with special emphasis on copyright and patent reform. Gerson is an active member: “I’ve been managing local campaigns for the election,” he told me. “And I’ve been working a lot with the Young Pirates Association—the youth wing of the Party.”

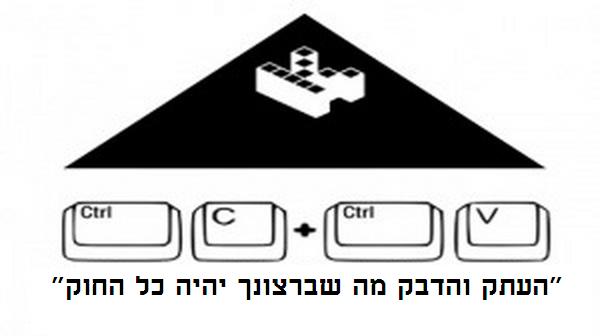

The Missionary Church of Kopimism picks up where Piratbyrån left off: it has taken the values of Swedish Pirate movement and codified them into a religion. They call their central sacrament “kopyacting,” wherein believers copy information in communion with each other, most always online, and especially via file-sharing. Ibi Botani’s kopimi mark—a stylized “k” inside a pyramid—is their religious symbol, as are CTRL+C and CTRL+V. Where Christian clergy might sign a letter “yours in Christ,” Kopimists write, “Copy and seed.” They have no god.

“We see the world as built on copies,” Gerson told me. “We often talk about originality; we don’t believe there’s any such thing. It’s certainly that way with life—most parts of the world, from DNA to manufacturing, are built by copying.” The highest form of worship, he said, is the remix: “You use other people’s works to make something better.”

Fittingly, it was exactly this kind of collaborative spirit that led to the founding of the Missionary Church of Kopimism. In

a blog post last week, Peter Sunde, one of the founders of The Pirate Bay, suggested that Kopimism as a religion had originated from a comment made by one of its opponents. Several years ago, he wrote, a Swedish lawyer for the M.P.A.A. was asked about file-sharing advocates. She replied, “It’s just a few people, very loud. They’re a cult. They call themselves Kopimists.” Sunde thought this cult business sounded like a good idea, and looked into registering Kopimism as a religion, but never followed through. Gerson did. “This is one of the essential things with how the internet and kopimism works,” Sunde wrote. “If you don’t do it, someone else will.”

In Sweden, the separation of church and state became law on January 1, 2000, the day that the Lutheran Church of Sweden stopped being the official state church. Since then, a government agency called the Kammarkollegiet has accepted applications for the legal recognition of religions. “They don’t make any kind of assessment of what the beliefs are, and the association is not sanctioned by the state,” Anders Bäckström, a professor of the sociology of religion at Uppsala University, told me. But the recognition of Kopimism, he said, is “a new situation. We haven’t seen anything of its kind before.” The most comparable previous effort was in 2008, when Carlos Bebeacua, a Uruguayan artist living in Sweden, attempted to register the Church of the Madonna of the Orgasm. The Kammarkollegiet refused his application, and in 2010 the Administrative Court of Appeal

upheld the rejection, arguing that the “madonna” (but not the “orgasm”) part of the church’s name would “cause offense not only in the broad groups of the population that have Christian roots, but also in society as a whole.”

Kopimism apparently raised no such qualms. Or maybe the Kopimists are just better than the Orgasmists at filling out government paperwork. “It’s exactly the same process as registering a business company,” Professor Bäckström said. But he thinks it’s unlikely that Kopimism’s success will inspire a flood of new applications. “In Sweden, we have many small New Age groups, but most of them have made no effort to be recognized,” he said. “Being recognized might mean they are opened to government scrutiny.”

For the Missionary Church of Kopimism, which holds up privacy as one of its chief values, such scrutiny could be a big problem, and it’s not clear what they’ll gain from registration. “We don’t really get any formal rights or benefits,” Gerson said. “We can apply for the right to marry people. There is government aid we can apply for, but we have no such plans today. I don’t, at least.” Rick Falkvinge, the Pirate Party founder,

speculated that if the Church incorporated the seal of confession into its rites, members could take advantage of the confidentiality that comes with certain privileged conversations. Generally, though, Sweden offers few legal exemptions for religious practice. No one, Gerson included, has any expectation that registration will exempt Church members from copyright law. “What the registration has done mostly is strengthen our identity,” Gerson said. “I think it will be easier to find new members now that we’re recognized.”

I asked him if he’d seen a boost in converts since the news broke. “I actually haven’t checked,” he said. “If you want I could do it right now.” There was a pause while he logged on to the registry: to join the Missionary Church of Kopimism simply requires filling out

an online form, as easy as signing up for a mailing list. “Right now we have a little more than four thousand,” he said, with no particular enthusiasm. “We got twelve hundred new members in the last week.”

Gerson told me that religious persecution is a “big concern” for the church’s adherents. “We all fear going to court for copyright infringement,” he said. This, of course, has been a worry for file-sharers long before it was formalized as a religion. What the Missionary Church of Kopimism has done is almost a reverse of how religious persecution usually works: whereas religions have often turned to protest because they feel persecuted, Gerson and his followers, feeling persecuted, turned to religion, in order to reframe and get attention for their protest. (It may sound silly to speak of file-sharing in terms of persecution, but when you think of the case of

Thomas Drake, or of Bradley Manning, it seems a little less silly.) And Kopimism is hardly the only faith to have been inspired or shaped by a particular political cause. The Rastafari movement, for example, is as much an anti-colonial resistance movement as it is a religion.

When Gerson talks about Kopimism as a religion, his tone is good-humored, but he also comes off as disarmingly sincere. Even if this religious-registration business is just a bit of political theatre, there’s no doubt that there’s an honestly and deeply held conviction at its core: the free exchange of information as a fundamental right. But is that enough to make it a genuine religion? When I asked Professor Bäckström, he hesitated. “Today you can believe in anything, so I suppose the idea of belief is a minor issue in a Northern European setting,” he said. “Belief can be a very wide concept.” He admitted, though, that he suspects that Kopimism is primarily an activist prank.

“I don’t think it’s a joke at all,” Gerson told me. “I think that many religions have been ridiculed over the years. I don’t think we’re the first to experience it.” The pirate movement’s political arm, the Pirate Party, provides one possible future path for Kopimism. People didn’t take the Pirate Party seriously at first, either. Then its membership exceeded that of the Green Party, and then the Liberal Party and the Christian Democrats, and then the Centre Party, and then the Young Pirates Association became the largest youth organization of any Swedish political party, and then several other parties and a number of prominent politicians shifted their stances on piracy in a more pirate-friendly direction, and then the Party spread to forty countries. Now the Pirate Party actually holds two seats in the European Parliament. These are early days for the Missionary Church of Kopimism. Who can say how far its gospel will spread?